V体育安卓版 - Intubating intensivists decrease emergency physician and anesthesiologist interruptions: a single-site retrospective cohort study

Highlight box

Key findings

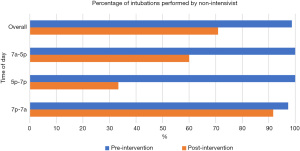

• In this single-site cohort study, a community hospital implemented intubating intensivists to a staffing model of a critical care unit. By staffing with intubating intensivists, the hospital showed a 27. 8% decrease in intubations performed by a non-intensivist V体育官网入口. When stratified by time of day, the greatest decreases were seen between 7 am to 5 pm (40% decrease) and 5 pm to 7 pm (67% decrease).

What is known and what is new?

• Little is known with regard to the performance of endotracheal intubation in community hospitals, and the procedure may be performed by intensivists, emergency physicians, anesthesiologists, respiratory therapists, or other clinicians. Performance of this procedure by non-intensivists may result in interruptions for the proceduralist called to perform the procedure in the intensive care unit (ICU) VSports在线直播.

• This manuscript reports an implementation of a staffing model into a community hospital ICU that resulted in a significant decrease in the proportion of intubations performed by a non-intensivist, suggesting decreased workload and interruptions for those specialties who were previously called to intubate in the ICU, emergency physicians and anesthesiologists.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This study implies that adopting an intubating intensivist decreases interruptions to other intubating specialties. Further work should quantify the time saved from interruptions and should examine safety outcomes from intensivist intubations VSports app下载.

Introduction

Background

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) and airway management is an essential and lifesaving procedure in the intensive care unit (ICU). However, it is a high-risk procedure that carries a significant risk of morbidity and mortality, particularly in the critically ill patient (1-5). Clinical experience is associated with higher rates of first-pass success in intubation (6-8) V体育官网.

Despite this, many community-level ICUs do not have 24/7 coverage by a fellowship-trained intensivist (9,10) which may result in performance of the procedure by a non-intensivist (11). Higher rates of adverse events during ICU intubations have been noted at night (10), which may be due to the emergent nature of the procedure, the delays involved in arranging a provider from outside the ICU, or the presence of a less-experienced practitioner performing the procedure. Additionally, intubations in the ICU are associated with higher risks of adverse events than other locations for emergent intubations such as the emergency department (ED) (5) VSports手机版.

Rationale and knowledge gap

In smaller community hospitals or during off-hours, management of the emergent airway is often the responsibility of an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist (12), emergency physician, or respiratory therapist (13), rather than the intensivist. However, little research has been published describing the characteristics of intubating clinicians in community hospitals which may have significant effects on other specialties who may be called emergently to the ICU to perform ETI. Deferring performance of this procedure to a non-intensivist physician increases interruptions in the workflow of the anesthesiologist or emergency physician—jobs which already experience significant interruptions (14,15)—and draws the anesthesiologist or emergency physician away from their primary role, which presents a potential for patient harm.

Objective

We hypothesized that implementing an intubating intensivist into the staffing model of the ICU would decrease the proportion of intubations performed by a non-intensivist. This in turn, would decrease the proportion of intubations performed in the ICU by the emergency physician and anesthesiologist, thereby decreasing interruptions to the ED and operating room. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-149/rc).

V体育ios版 - Methods

Study site

Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital (BWFH) is a 171-bed community hospital located in Boston, MA with approximately 32,700 ED visits per year. BWFH has critical-care-fellowship-trained intensivists in-house during daytime hours and may have critical care or non-critical-care trained physicians in-house at night. Airway management in the ICU is managed by a different practitioner according to the time of day, as shown in Table 1. During the day, coverage is shared by anesthesiology and emergency medicine (EM), while at night, primary coverage is provided by respiratory therapy (RT) with EM as a backup or for difficult airways.

Table 1

| Time of day | Intubating specialty |

|---|---|

| 7:00 am–5:00 pm | Primary: anesthesiology |

| Backup: emergency medicine | |

| 5:00 pm–7:00 pm | Emergency medicine |

| 7:00 pm–7:00 am | Primary: respiratory therapy |

| Backup: emergency medicine |

V体育2025版 - Intervention

This was a pre- and post-intervention retrospective cohort study. Prior to the intervention, all intensivists at BWFH were trained in pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) but did not routinely perform ETI. After a six-month trial period (January 2022–July 2022) where one emergency physician intensivist (EPI) was integrated into the BWFH intensivist staffing pool, a total of four intubating physicians (one PCCM-trained intensivist and three EPIs) were included in the ICU staffing from July 2022–present. Although the intubating intensivist primarily provided daytime intensivist coverage, they also provided occasional overnight coverage as needed. The intubating intensivist had primary responsibility for airway management on shift, although backup could be called for anticipated difficult airways.

"VSports" Data analysis

Data were abstracted from the electronic medical record (EMR; Epic Systems, Verona, WI, USA). For all patients admitted to the BWFH ICU during the study period, a structured query was made through the EMR to abstract all procedure notes for either “intubation” or “airway management”, which are the two primary ways that ETI is documented in the EMR, depending on the mode of documentation and data entry utilized. All intubations between January 2021 to December 2021 were included in the pre-intervention period and between July 2022 to June 2023 in the post-intervention period. All patients admitted to the BWFH ICU were eligible for inclusion. Patients are admitted to the ICU after consultation with the attending intensivist; there are no formal inclusion or exclusion criteria for ICU admission.

The date and time of the intubation, proceduralist name, and specialty were abstracted from the procedure note. For procedure notes documented by emergency physicians, the EMR was reviewed to ensure that the airway was performed in the ICU, and not in the ED with delayed documentation at a later date when the patient was in the ICU. For procedure notes documented by EPIs, the staff schedule and EMR were reviewed to ensure that the procedure was performed while the EPI was working in the ICU and not in the ED. For procedures documented by trainees or physician assistants, the supervising physician specialty was utilized.

With regards to time of day, any time a procedure was documented within two hours after the change in airway management responsibility (e.g., any procedures between 5 pm and 7 pm for the 5 pm change in responsibility) the documented time of paralytic administration was used as the timestamp for the procedure to ensure that notes documented after the procedure were attributed to the proper time of day.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using R (R Foundation, Version 4.3.1). Chi-squared analysis was used to compare proportions of groups between time periods. After overall proportions were calculated, we examined the results by time of day, given the different staffing patterns and responsibilities for performing ETI. We used a P value of <0.05 (two-sided) for statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mass General Brigham (Protocol 2024P000541, March 2024) and determined to be exempt from written informed consent as no identifying information was collected. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Results

A total of 134 intubations were documented during the study period, 79 during the pre-intervention period and 55 during the post-intervention period. In the pre-intervention period 78 (98.7%) of the intubations were performed by a non-intensivist, while in the post-intubation period 39 (70.9%) were performed by a non-intensivist (Figure 1). This 27.8% decrease was statistically significant (χ2=22.6, P<0.001), confirming our hypothesis. Full results by intubating specialty and time of day are shown in Table 2.

VSports在线直播 - Table 2

| Specialty | Number of intubations | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | |

| 7 am to 5 pm | N=36 | N=25 |

| Anesthesiology | 23 (63.9%) | 14 (56.0%) |

| Emergency medicine | 13 (36.1%) | 1 (4.0%) |

| EM-CCM | 0 (0%) | 8 (32%) |

| Non-EM CCM | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.0%) |

| 5 pm to 7 pm | N=6 | N=6 |

| EM | 6 (100%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| EM-CCM | 0 (0%) | 4 (67.7%) |

| 7 pm to 7 am | N=37 | N=24 |

| EM | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| EM-CCM | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.3%) |

| Non-EM CCM | 1 (2.9%) | 0 |

| RT | 35 (94.6%) | 22 (91.7%) |

CCM, critical care medicine; EM, emergency medicine; RT, respiratory therapy.

7 am to 5 pm

In the pre-intervention period, there were a total of 36 intubations from 7 am to 5 pm, with 23 (63.9%) performed by anesthesiology and 13 (36.1%) performed by emergency medicine; no intubations were performed by the intensivist. In the post-intervention period, there were a total of 25 intubations, of which 15 (60%) were performed by a non-intensivist. The difference between these groups was statistically significant (χ2=17.2, P<0.001). Of these intubations, anesthesiology performed 14 (56%) while emergency medicine performed 1 (4%). Ten intubations (40%) were performed by the intensivist; eight (32%) of which were performed by an EPI and 2 (8%) of which were performed by a pulmonary and critical care intensivist.

5 pm to 7 pm

In the pre-intervention period, there were a total of 6 intubations between 5 pm to 7 pm, all 6 of which (100%) were performed by emergency medicine. In the post-intervention period, there were a total of 6 intubations, with 2 (33.3%) performed by emergency medicine and 4 (66.7%) performed by the intensivist. All these intensivist intubations were performed by an emergency physician. This difference was statistically significant (χ2=6, P=0.014).

7 pm to 7 am

In the pre-intervention period, there were a total of 37 intubations performed between 7 pm to 7 am, of which 36 (97.5%) were performed by a non-intensivist. RT performed 35 (94.6%) of the intubations, while 1 (2.9%) was performed by emergency medicine and 1 (2.9%) was performed by a non-emergency-medicine intensivist. In the post-intervention period, there were a total of 24 intubations. RT performed 22 (91.7%) of the intubations, while 2 (8.3%) were performed by an EPI. The difference between intubations performed by the intensivist and non-intensivist failed to meet the threshold for statistical significance (χ2=0.98, P=0.32).

"V体育官网入口" Discussion

Key findings

Little published data describes characteristics of ETI in community hospitals and the effect of intubating specialty on workflow has not been explored. In this single center pre- and post- study, implementation of an intubating intensivist into the staffing of the ICU led to a significant decrease in the proportion of intubations performed by a non-intensivist, supporting our hypothesis. The greatest decrease in intubations performed by a non-intensivist was in the specialty of emergency medicine, suggesting a significant decrease in the interruptions that require the emergency physician to leave the patients in ED to intubate in the ICU.

Explanation of findings

Overall, the number of intubations decreased from 79 to 55 between the two time periods. The reason for this decrease is unknown and may reflect changes in patient acuity, temporal trends during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, practice patterns of staff changes, or another confounding factor.

The greatest effect of this implementation was seen during the daytime hours of 7 am to 5 pm, where there was a reduction in the rate of intubations performed by emergency medicine from 36.1% to 4%, a 32.1% decrease in the overall percentage of intubations performed by the ED and 88.9% relative decrease in the proportion of time that the emergency physician was called to the ICU to intubate. Nearly all of this reduction was due to an increase in intubations performed by EPIs (from 0% to 32%), suggesting that intubations performed by EPIs replaced intubations that would otherwise be performed by the emergency physician. There was a smaller decrease in the rate of anesthesiology-performed intubations, from 63.9% to 56.0% (−7.9%) which also corresponded to the increase in non-emergency intensivist intubations (an increase from 0% to 8%); this may suggest that the non-emergency intensivist intubations replaced the need for anesthesiology support. Regardless of the fellowship training of the intubating intensivist, the decrease in the percentage of non-intensivist performed intubations suggests a significant decrease in the interruptions experienced by the ED (and to a lesser extent, the anesthesiologist).

During the hours of 5 pm to 7 pm, there was a decrease in the number of intubations performed by a non-intensivist provider (100% versus 33%). All of these intubations were performed by the EPI, suggesting a significant reduction in interruptions to the emergency physician during this particularly busy time of day in the ED. However, the limited number of intubations during this period limits our ability to draw firm conclusions about the data.

The night-time hours failed to show any difference in the proportions of intubations performed by the intensivist. There are several possible reasons for this. The first is that intubating intensivist coverage was heavily weighted towards the daylight hours. The second is that there was an institutional desire to maintain the skill set of the intubating respiratory therapist; it is possible that some RT intubations were supervised by an intubating physician but may have been missed if there was no attestation or notation that the physician was present for the procedure.

Strengths and limitations

Little published work describes intubation by specialty in community hospitals. In the present work, we describe our workflow, staffing model, and include all recorded intubations during a two-year period. To our knowledge, no other facility has reported similar data. Strengths of this work include the diverse staffing model, reliance on the electronic medical record for data abstraction, and the convenience of a natural experiment that occurred with the change in a staffing model.

There are several limitations to this study. The first is that this is a single site study and local practice patterns may limit external generalizability. Also, only documented notes were used to identify intubations, so if they were performed without a documented procedure note, they would not be included in the analysis. In addition, the pre-test period included a portion of the COVID pandemic where COVID was more prevalent which may have biased the data; while there was an increased number of intubations during this period, it is unclear whether this would have biased the data towards or away from our hypothesis. We also did not assess time spent on the task of intubation, which would address the duration of interruption spent by the intubating clinician. Finally, although procedural success and procedure related complications during and immediately following emergency airway management are important to consider, this data was not collected for this study. Thus, this study cannot be used to assess safety and efficacy of intensivist performed intubations.

Comparisons with similar research

To our knowledge, we are the first institution to report our staffing model. We were not able to identify any other published research describing the primary operator for ETI in the ICU. Therefore, we cannot draw any comparison between this work and practices at other community hospital ICUs.

Implications and actions needed

Although competence in airway management is mandated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), many graduates of PCCM fellowship training programs report a lack of opportunities to gain experience in ETI (16) and therefore many graduating fellows do not feel proficient in ETI upon graduation (17,18). This may explain the relative proportion of intubations that were performed by an anesthesiologist during daylight hours, despite the presence of a board-certified intensivist in-house.

Recently, the proportion of emergency physicians who choose to seek further training in critical care medicine has increased the prevalence of EPIs (19-21). As airway training is a core part of emergency medicine training, EPIs are experts in airway management. This is shown in our data, as EPIs were responsible for 14 of the 17 (82%) of the intubations performed by intensivists.

A significant proportion of intubations were performed by RT in our study. This may reflect institutional practice patterns at smaller community hospitals (22). Our study was not designed to evaluate the effect of intubating intensivists on the proportion of intubations performed by RT and no conclusions can be drawn.

Overall, the appropriate clinician to perform ETI in the ICU is unknown. We would argue that an intubating intensivist has the best balance between knowledge of the patient and their conditions, experience with resuscitation of the critically ill, and technical expertise with critical procedures. However, many ICUs do not have intubating intensivists on staff, or may not have 24-hour intensivist coverage, so alternate protocols must be implemented. Both emergency physicians and anesthesiologists are adept at ETI, but have other responsibilities that are interrupted when called to intubate in the ICU. Respiratory therapists have significant comfort with the mechanical ventilator, but they are not trained to manage hemodynamics or resuscitation, and acquiring a volume of appropriately-supervised intubations to achieve competence may be difficult.

Conclusions

In this single site study, we showed that introducing intubating intensivists into the staffing model of a community hospital decreased the proportion of intubations performed by non-intensivists. The greatest decrease was shown during daylight hours, when intubations performed by emergency physicians were nearly eliminated in favor of intubations performed by intensivists. These data suggest that implementation of intubating intensivists decreases the rate of interruptions to emergency physicians and anesthesiologists who may otherwise have been called to the ICU to intubate. Community hospitals with ICUs may choose to implement an intubating intensivist model to reduce reliance on other non-intensivist clinicians to perform ETIs. If a non-intubating intensivist model is chosen, hospitals should be aware of the interruptions placed on the clinician required to intubate in the ICU. Further research should explore impacts on workflow for clinicians called emergently to the ICU to intubate.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-149/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-149/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-149/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-149/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mass General Brigham (Protocol 2024P000541, March 2024) and determined to be exempt from written informed consent as no identifying information was collected. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Russotto V, Myatra SN, Laffey JG, et al. Intubation Practices and Adverse Peri-intubation Events in Critically Ill Patients From 29 Countries. JAMA 2021;325:1164-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russotto V, Tassistro E, Myatra SN, et al. Peri-intubation Cardiovascular Collapse in Patients Who Are Critically Ill: Insights from the INTUBE Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206:449-58. [VSports手机版 - Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosier JM, Sakles JC, Law JA, et al. Tracheal Intubation in the Critically Ill. Where We Came from and Where We Should Go. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:775-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hickey AJ, Cummings MJ, Short B, et al. Approach to the Physiologically Challenging Endotracheal Intubation in the Intensive Care Unit. Respir Care 2023;68:1438-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downing J, Yardi I, Ren C, et al. Prevalence of peri-intubation major adverse events among critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta analysis. Am J Emerg Med 2023;71:200-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung W, Kim J. Factors associated with first-pass success of emergency endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:109-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanders RC Jr, Giuliano JS Jr, Sullivan JE, et al. Level of trainee and tracheal intubation outcomes. Pediatrics 2013;131:e821-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buis ML, Maissan IM, Hoeks SE, et al. Defining the learning curve for endotracheal intubation using direct laryngoscopy: A systematic review. Resuscitation 2016;99:63-71. ["V体育官网" Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nizamuddin J, Tung A. Intensivist staffing and outcome in the ICU: daytime, nighttime, 24/7? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2019;32:123-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burchardi H, Moerer O. Twenty-four hour presence of physicians in the ICU. Crit Care 2001;5:131-7. ["VSports最新版本" Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller AG, Mallory PM, Rotta AT. Endotracheal Intubation Outside the Operating Room: Year in Review 2023. Respir Care 2024;69:1165-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walz JM. Point: Should an anesthesiologist be the specialist of choice in managing the difficult airway in the ICU? Yes. Chest 2012;142:1372-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thalman JJ, Rinaldo-Gallo S, MacIntyre NR. Analysis of an endotracheal intubation service provided by respiratory care practitioners. Respir Care 1993;38:469-73. ["V体育官网入口" PubMed]

- Henry ES. Task interruptions in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Australas 2022;34:1019-20. ["V体育官网入口" Crossref] [PubMed]

- Werner NE, Holden RJ. Interruptions in the wild: Development of a sociotechnical systems model of interruptions in the emergency department through a systematic review. Appl Ergon 2015;51:244-54. ["V体育2025版" Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brady AK, Brown W, Denson JL, et al. Variation in Intensive Care Unit Intubation Practices in Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine Fellowship. ATS Sch 2020;1:395-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown W, Santhosh L, Brady AK, et al. A call for collaboration and consensus on training for endotracheal intubation in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care 2020;24:621. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chichra A, Naval P, Dibello C, et al. Barriers to Training Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellows in Emergency Endotracheal Intubation Across the United States. Chest 2011;140:1036A. ["V体育安卓版" Crossref]

- Huang DT, Osborn TM, Gunnerson KJ, et al. Critical care medicine training and certification for emergency physicians. Crit Care Med 2005;33:2104-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayglothling JA, Gunnerson KJ, Huang DT. Current practice, demographics, and trends of critical care trained emergency physicians in the United States. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:325-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strickler SS, Choi DJ, Singer DJ, et al. Emergency physicians in critical care: where are we now? J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2020;1:1062-70. ["V体育官网" Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller AG, Gentile MA, Coyle JP. Respiratory Therapist Endotracheal Intubation Practices. Respir Care 2020;65:954-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Jansson PS, Hallisey SD, Aisiku IP, Sajjad H, Sanchez LD, Seethala RR. Intubating intensivists decrease emergency physician and anesthesiologist interruptions: a single-site retrospective cohort study. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2025;9:19.